Welcome to our exploration of the profound lessons learned from the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. This article delves into the transformative impact of the disaster on our understanding of recovery, environmental stewardship, and the power of local knowledge.

Reflections on the Indian Ocean Tsunami and its Enduring Impact on Global Disaster Management

Imagine a scene that begins with sheer devastation—coastlines swallowed by towering waves, boats scattered like matchsticks, and entire communities reduced to debris. The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, triggered by one of the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded, left behind a trail of destruction that was both horrifying and humbling. The waves, which reached heights of up to 30 meters, claimed over 230,000 lives across multiple countries, making it one of the deadliest natural disasters in history.

Now, juxtapose this image of ruin with the indomitable spirit of resilience that emerged in the aftermath. Picture locals sifting through the remnants of their homes, not just to mourn, but to salvage and rebuild. International aid poured in, and with it, a global outpouring of support that transcended borders and languages. Slowly but surely, new structures began to rise above the wreckage, symbolizing hope and renewal.

Envision the stark contrast between the desolate landscapes left by the tsunami and the vibrant scenes of reconstruction. Schools, hospitals, and homes were rebuilt, each brick laid with determination and each beam raised with hope. The echoes of loss will forever linger, but so will the testament to human tenacity. This dual image serves as a poignant reminder of nature’s power and the enduring capacity of the human spirit to heal, rebuild, and look towards a better future.

The Aftermath of Devastation

In the stark light of day on December 26, 2004, the world awoke to the horrifying reality of one of the most devastating natural disasters in recorded history. The tsunami, triggered by a massive undersea earthquake off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, had swept across the Indian Ocean, leaving an unfathomable trail of destruction in its wake. The immediate aftermath was nothing short of apocalyptic. Entire coastal communities were reduced to matchsticks, the raw power of the waves having flattened buildings, upturned vehicles, and snapped trees like twigs. The sheer scale of destruction was overwhelming: thousands of lives lost, countless more missing, and untold numbers of people displaced from their homes.

The waves, which reached heights of up to 30 feet, spared no one and nothing in their path. Beaches that were once teeming with tourists became unrecognizable wastelands, littered with debris and detritus. Fishing villages, their livelihoods intrinsically linked to the sea, were ironically swallowed whole by the very source of their sustenance. Infrastructure was not just damaged, but utterly decimated; roads, bridges, and communication networks vanished, making the true extent of the devastation painfully slow to emerge.

For response teams, the challenges were immediate and immense. Access to affected areas was severely hindered by the destruction, making the crucial first hours and days a logistical nightmare. Helicopters became a lifeline, the only viable means of reaching isolated communities and assessing their needs. The initial priorities were clear but daunting:

- Search and rescue operations to find survivors trapped under rubble or stranded in remote areas.

- Provision of urgent medical care to the injured.

- Distribution of food, water, and shelter to those left homeless.

- Prevention of disease outbreaks due to contaminated water and decomposing bodies.

Yet, even as aid began to trickle in, the magnitude of the disaster continued to unfold. The lack of clean water and sanitation facilities posed an immediate health risk. Fears of disease outbreaks loomed large, as the tropical climate and the sheer number of bodies, both human and animal, created a breeding ground for infections. The psychological trauma was equally profound; survivors grappled with the loss of loved ones, homes, and livelihoods, their worlds irrevocably altered by the tsunami’s fury.

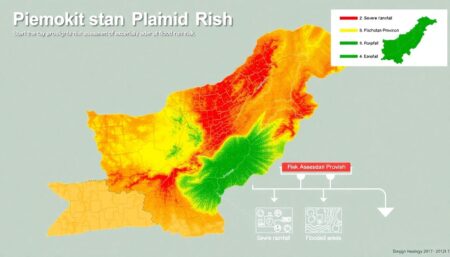

Lessons Learned: Environmental and Social Impacts

The devastating power of a tsunami is not confined to the immediate destruction it causes. The environmental impact is immense, with waves stripping away coastal vegetation, eroding shorelines, and causing extensive habitat destruction. Moreover, the saltwater inundation can render soil infertile, making it unusable for agriculture for years to come. The social impacts are equally severe. Communities are often displaced, leading to overcrowding in relief camps and putting strain on resources. The trauma of the event can leave deep emotional scars, with survivors experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) long after the waters have receded.

The early recovery efforts after a tsunami are crucial, but unfortunately, they are often marred by missteps. In the rush to provide aid, poor planning and coordination can lead to ineffective use of resources. For instance, relief supplies may be misallocated, with some areas receiving duplicate aid while other, more needy regions go overlooked. Furthermore, the influx of well-meaning but uncoordinated volunteers and organizations can overwhelm local authorities, creating more chaos than help. Here are some common mistakes:

- Lack of coordination among aid agencies leading to duplicated efforts and gaps in coverage.

- Ignoring local knowledge and expertise in favor of external solutions.

- Unsustainable and inappropriate construction of temporary shelters and infrastructure.

- Overlooking long-term needs in favor of immediate relief.

These missteps can have long-term consequences. Inadequate or inappropriate housing can leave survivors in a state of prolonged limbo, unable to truly restart their lives. The lack of coordination can also result in some communities receiving far less aid than others, creating disparities and exacerbating social tensions. Additionally, the focus on immediate relief can often mean that long-term needs, such as livelihood restoration and mental health support, are overlooked.

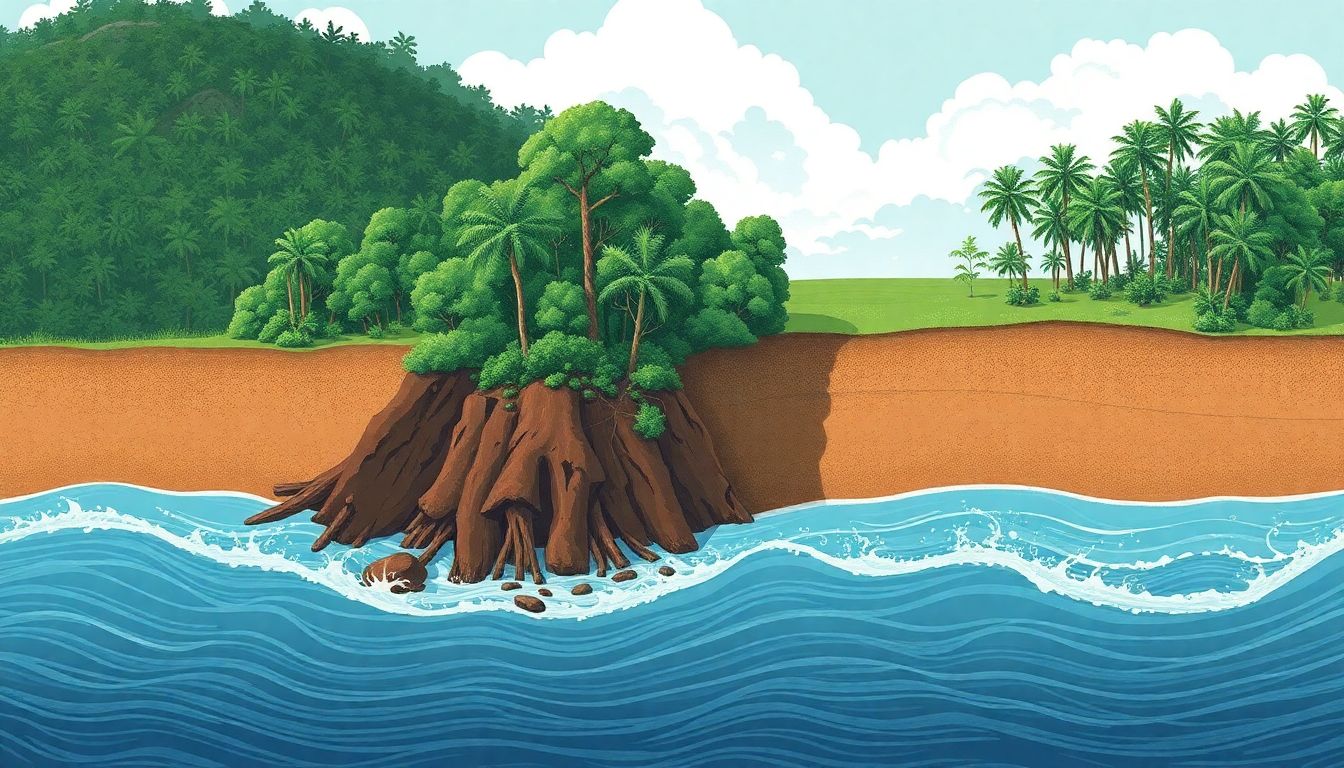

Environmentally, hasty recovery efforts can also do more harm than good. The rush to rebuild can lead to poorly planned infrastructure that is not resilient to future disasters. Moreover, the destruction of natural habitats, such as mangroves and coral reefs, which can act as natural barriers to tsunamis, can make communities even more vulnerable to future events. It is therefore vital that recovery efforts are not only swift but also sustainable and well-coordinated, taking into account both the immediate and long-term needs of affected communities and the environment.

Nature-Based Solutions and Localization

In recent years, there has been a significant shift towards nature-based solutions and localization in disaster recovery. Traditional methods often involve heavy engineering and infrastructure, but communities around the world are increasingly embracing nature’s innate abilities to mitigate disaster impacts. Nature-based solutions use natural and nature-engineered systems to address societal challenges, including those related to disasters. This shift is not just about environmental consciousness; it’s about harnessing the power of nature to create more resilient and sustainable communities.

One successful example is the mangrove restoration project in Vietnam. Mangroves act as natural barriers against storm surges and tsunamis. The project, initiated by the government and supported by international organizations, has seen the planting of millions of mangrove trees along the coast. This has not only increased the country’s resilience to disasters but also provided additional benefits such as carbon sequestration and habitat restoration. Similarly, the Netherlands has adopted a policy of ‘Room for the River,’ where instead of merely building higher levees, they are widening rivers, creating floodplains, and even moving dykes to give rivers more room to flood safely.

Localization is another key aspect of this shift. It involves empowering local communities to plan, implement, and manage their own disaster recovery processes. This approach ensures that solutions are tailored to the specific needs and context of the community. A great example of this is the community-based disaster risk management program in Bangladesh. This program has helped communities develop their own disaster response plans, early warning systems, and risk mitigation strategies. By putting the power in the hands of local people, this approach has proven to be more effective and sustainable.

Another inspiring example is the Green Legacy Hiroshima initiative in Japan. This project involves planting trees and creating green spaces in areas devastated by the atomic bomb. It’s a testament to the power of nature to heal and restore, even in the most challenging circumstances. The initiative has not only helped to revitalize the environment but also provided a sense of hope and renewal to the community. These examples demonstrate the potential of nature-based solutions and localization in disaster recovery. They show that by working with nature and empowering communities, we can create more resilient and sustainable futures. Here are some key benefits of these approaches:

- Cost-effectiveness

- Environmental sustainability

- Community empowerment

- Cultural appropriateness

Building Forward: Integrating Climate Considerations

In the wake of natural disasters, communities are increasingly recognizing the importance of integrating climate considerations into recovery planning. This forward-thinking approach isn’t just about rebuilding what was lost; it’s about rebuilding smarter and more resiliently. By factoring in climate projections, such as increased frequency of extreme weather events, recovery plans can anticipate future risks and mitigate them today. This could mean restoring wetlands to act as natural buffers against storm surges, or reinforcing buildings to withstand stronger winds. By doing so, communities can break the cycle of ‘build, destroy, rebuild’ and instead create a more sustainable future.

The intersection of natural infrastructure and innovative engineering is where true resilience lies. Natural infrastructure, such as mangroves, coral reefs, and forests, has proven time and again to be a powerful defense against natural disasters. Mangroves, for instance, can absorb up to 90% of wave energy, significantly reducing the impact of storm surges. Meanwhile, innovative engineering solutions, like floating homes or amphibious buildings, can complement natural infrastructure by providing adaptable solutions in high-risk areas.

Let’s consider some examples of this integrated approach:

- In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, New York City implemented a $20 billion climate resilience plan that includes both natural and engineered solutions, such as restoring wetlands and installing flood barriers.

- Following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, Sri Lanka initiated a ‘Green Belt’ program, planting 75,000 mangrove saplings to protect coastal communities.

- The Netherlands, a country largely below sea level, has long pioneered innovative engineering solutions, like the Maeslant Barrier, a massive movable storm surge barrier.

However, it’s crucial to remember that community engagement is as important as the technical aspects. Disaster recovery planning should always include local stakeholders, ensuring that solutions are culturally appropriate, economically viable, and socially just. After all, resilience is not just about infrastructure; it’s about people. By combining climate considerations, natural infrastructure, innovative engineering, and community engagement, we can create a holistic approach to disaster recovery that truly builds for the future.

FAQ

What were the immediate challenges faced by response teams after the 2004 tsunami?

How did early recovery efforts exacerbate the crisis?

- Relocating communities to areas at higher risk from future disasters.

- Debris piled near shorelines, suffocating ecosystems.

- Rapid overexploitation of resources, triggering soil erosion and landslides.

- Influx of fishing gear and boats, straining local marine ecosystems and fueling conflicts among fisherfolk.