Welcome to this captivating exploration of the ecological impact of the ‘warm blob’ marine heat wave on Alaska’s common murres. This article delves into the devastating consequences of this environmental phenomenon, highlighting the importance of understanding and mitigating the effects of climate change on our ecosystems.

Unveiling the Devastating Impact of Marine Heat Waves on Alaska’s Common Murres

Imagine a rugged, windswept cliff face in Alaska, teeming with life—a bustling metropolis of common murres. These tuxedoed seabirds, with their sharp black and white plumage, huddle together in dense clusters, the air filled with their guttural calls. They are here for one purpose: to breed and raise their young, in a colony that stretches as far as the eye can see.

The backdrop to this spectacle is the vast, restless ocean. It sprawls out, a shimmering expanse of deep blue, but there’s something different about it today. It’s warmer than usual, a change that’s barely perceptible to the casual observer, but the murres seem to sense it. They take flight, plunging into the waters, only to return with less bountiful catches than years past.

There’s a hint of something sinister lurking beneath the surface—the ‘warm blob,’ an anomaly of heated water that’s wreaking havoc on the ecosystem. It’s pushing the murres’ prey further into the depths, forcing these hardy birds to work harder, to fly further, to dive deeper. The colony is a live microcosm, a stage where the drama of a changing climate plays out, one dive at a time.

The Warm Blob Phenomenon

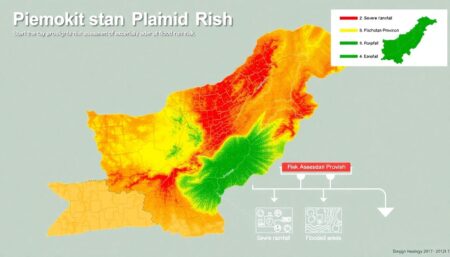

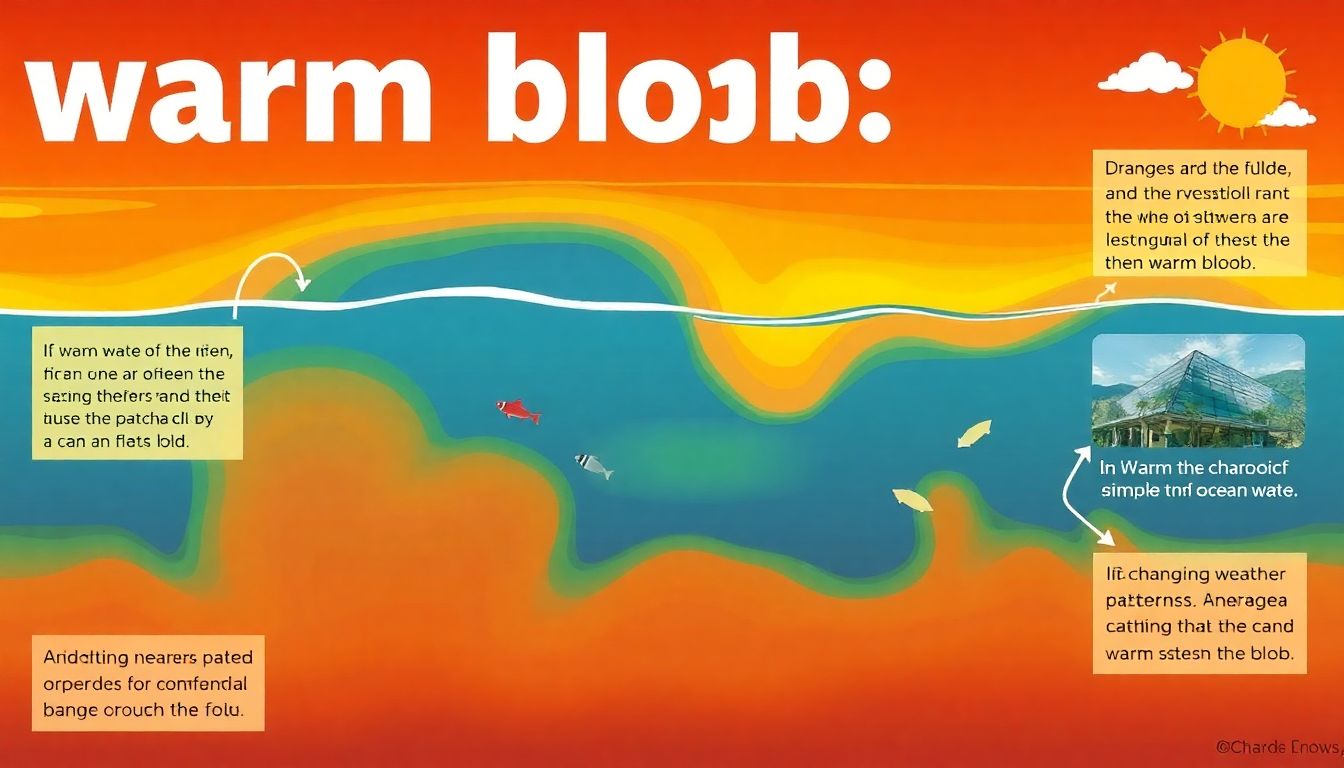

In the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, an unusual phenomenon has been occurring—a marine heat wave known as the ‘warm blob‘. This isn’t your typical warm current; it’s a massive, persistent area of warm water that has been disrupting the ocean’s ecosystem since 2013. The warm blob first appeared off the coast of Alaska and has since been wreaking havoc on the delicate balance of marine life.

So, what’s causing this gigantic warm blob? Scientists point to a few factors:

- A persistent high-pressure ridge that has been lingering over the Pacific Coast, leading to calmer waters and more sunlight penetration, thus warming the surface.

- A shift in wind patterns, which has reduced the usual wind-driven upwelling that brings cooler, nutrient-rich water to the surface.

- Climate change, which is exacerbating these conditions and making marine heat waves more frequent and severe.

The impact of the warm blob on the ocean ecosystem has been profound. The warmer waters have led to a decrease in phytoplankton, the base of the marine food chain. This has resulted in a cascade of effects, including a reduction in the availability of prey for larger species. One of the most dramatically affected species is the common murres in Alaska.

Common murres are small, black and white seabirds that rely on the abundance of forage fish, such as capelin and herring, to survive. The warm blob has led to a massive decline in these fish populations, causing a catastrophic breeding failure for the common murres. Between 2015 and 2016, thousands of murres were found washed up on Alaska’s shores, emaciated and starving. The lack of food has also led to reduced breeding success, with many murres unable to raise their chicks due to insufficient food resources. This ecological disaster is a stark reminder of the interconnectedness of the ocean ecosystem and the far-reaching impacts of marine heat waves.

Documenting a Crisis: Massive Murre Mortality

In the stark and windswept coastal landscapes of the Pacific Northwest, a silent crisis has been unfolding. The Common Murre, a typically resilient seabird, has been experiencing a significant mortality event that has left scientists and conservationists alike alarmed and eager for answers. Enter the UW-led Coastal Observation and Seabird Survey Team (COASST), a dedicated group of researchers and volunteers who have taken on the monumental task of documenting this unsettling phenomenon.

The methods used by COASST to quantify and understand the scope of this event are both innovative and meticulous. By combining systematic beach surveys, carcass collections, and necropsies, the team has been able to gather valuable data on the scale and potential causes of the die-off. Here’s a breakdown of their approach:

-

Beach Surveys:

Volunteers meticulously comb designated beach zones, counting and collecting carcasses to quantify the extent of the mortality event.

-

Carcass Examinations:

Collected specimens undergo necropsies to determine the cause of death, helping to identify any commonalities or patterns.

The findings of COASST and other observers paint a grim picture. Since 2015, thousands of Common Murres have been found dead along the coasts of Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, and California. This massive die-off isn’t just a localized event; it’s a coast-wide crisis that underscores a deeper ecological disturbance.

One of the most striking aspects of this mortality event is its magnitude and duration. While seabird die-offs are not uncommon, the sheer scale and prolonged nature of this event set it apart. Furthermore, the breadth of the affected area suggests that the cause isn’t a localized issue but rather a systemic problem affecting the broader marine ecosystem. As researchers continue to delve into the data, the implications of their findings could have far-reaching consequences for marine conservation efforts along the Pacific coast.

Measuring the Impact of Marine Heat Waves

Colony-based surveys have long been a staple in ornithological research, providing invaluable insights into seabird populations. To estimate total mortality, scientists meticulously count and analyzechanges in colony sizes over time. This involves visiting remote, often treacherous locations to gather data on breeding pairs, nests, and chicks. By comparing these numbers year over year, researchers can estimate not only the number of birds that return to the colony, but also make inferences about the overall health and mortality rates of the population.

The impact of mortality estimates goes beyond mere numbers; they serve as a bellwether for the broader ecosystem. For instance, consider the dramatic decline in murre populations in the Gulf of Alaska and the eastern Bering Sea. Murres, being high-trophic level predators, are sensitive to changes in prey availability. When their numbers plummet, it’s a clear indicator that something is amiss lower down the food chain. Colony-based surveys have revealed that murre populations in these regions have seen an alarming decline of up to 80-90% in recent decades.

Several factors contribute to this stark decline, as outlined by researchers:

- Changes in prey distribution and abundance, likely due to ocean warming and other climate-driven changes.

- Increased predation from eagles and other birds, which have seen their own populations grow.

- Incidental take in fisheries, which can claim thousands of birds each year.

- Massive die-off events linked to starvation and extreme weather.

The long-term impacts of these declines are not yet fully understood, but they underscore the need for continued monitoring and vigilance. Colony-based surveys remain one of our best tools for understanding and responding to these changes. They provide a window into the lives of these seabirds, and a lens through which we can better appreciate the complexities and challenges of the ecosystems they inhabit.

Climate Change and Seabird Survival

Climate change is reshaping our world in profound ways, and one of the most alarming transformations is occurring in our oceans, impacting the delicate web of marine life, particularly seabirds. These avian marvels are sentinels of ocean health, and their declining populations are ringing alarm bells for scientists worldwide.

One of the most concerning trends is the increasing frequency and intensity of marine bird mortality events. These events, known as ‘wrecks,’ occur when large numbers of seabirds are found dead or dying along shorelines. Several factors tied to climate change are exacerbating this issue:

- Rising sea temperatures are altering the distribution and abundance of prey species, making it harder for seabirds to find food.

- Increased frequency of extreme weather events can destroy breeding habitats and disrupt nesting seasons.

- Sea-level rise threatens to submerge low-lying nesting grounds, further endangering seabird populations.

The intensity of these mortality events is also escalating. For instance, in 2015-2016, a massive die-off of common murres in the Northeast Pacific resulted in the deaths of an estimated 500,000 to 1 million birds. This event, dubbed the ‘Blob‘, was a marine heatwave that led to a cascading ecosystem failure, illustrating the catastrophic impact of climate change on seabird survival.

Beyond the immediate fatalities, climate change is also driving long-term ecosystem rearrangement, reshuffling the intricate networks that seabirds rely on for survival.

- Shifting currents and warming waters are causing prey species to move or decline, making it harder for seabirds to feed.

- The timing of breeding seasons is being disrupted, leading to a mismatch between when chicks need food and when it’s available.

- The introduction of new predators or competitors can further destabilize ecosystems, putting additional pressure on seabirds.

This rearrangement can have cascading effects, altering food webs, nutrient cycling, and even the physical structure of ecosystems. Without significant global efforts to mitigate climate change, the future of many seabird species—and the ecosystems they inhabit—hangs in the balance.

FAQ

What is the ‘warm blob’ marine heat wave?

How did the ‘warm blob’ affect common murres?

What methods were used to document the murre mortality event?

What are the long-term impacts of marine heat waves on seabirds?

What can be done to mitigate the effects of marine heat waves on seabirds?

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions to slow down global warming and ocean warming.

- Support conservation efforts to protect seabird habitats and food sources.

- Invest in research and monitoring programs to better understand and predict marine heat waves.

- Encourage citizen science initiatives to gather data on seabird populations and health.